Aside from the debate over whether or not organic agriculture can feed the world, this is probably one of the most controversial topics related to organic farming. It’s been pretty well documented that good organic farming methods can improve and maintain soil health. There is a lot of evidence that plants grown on healthy soil will also be healthy and will have increased resistance to pests and diseases. But are organically produced foods healthier than conventional produce?

Many people today purchase organic fruits and vegetables because they almost always have lower levels of pesticide residues than their conventional counterparts. While there’s debate over whether or not the pesticide residues in conventional produce are partially responsible for the chronic ill health of many Americans, most people agree that eating organic produce does reduce pesticide exposure. A lot of people eat organic food mostly for what’s not in it.

Before most people were worried about pesticides, however, organic proponents claimed that organic food was healthier because it was grown on healthy soil. Sir Albert Howard, often considered the father of the organic farming movement, blamed the general ill health in England in the 1940s partially on poor farming practices that depleted soil fertility. This view was shared by others in the early British organic movement and has been held by many organic farmers ever since.

With seventy years more research on the possible connection between farming methods and human health, it would be reasonable to assume that we can now definitively state that Howard was either right or wrong in saying that people who ate organically grown vegetables would be healthier than those who did not. But it’s not that simple. The difficulty is that Howard and his successors never looked just at farming methods. They had a holistic perspective in which soil fertility, diet and nutrition were inseparable.

To understand why it’s always been hard to determine what effect farming methods have had on human health, we need to look back at the sources on which Howard and others drew when they claimed that organic food was superior — like the work of Sir Robert McCarrison.

McCarrison’s Vitamin Research

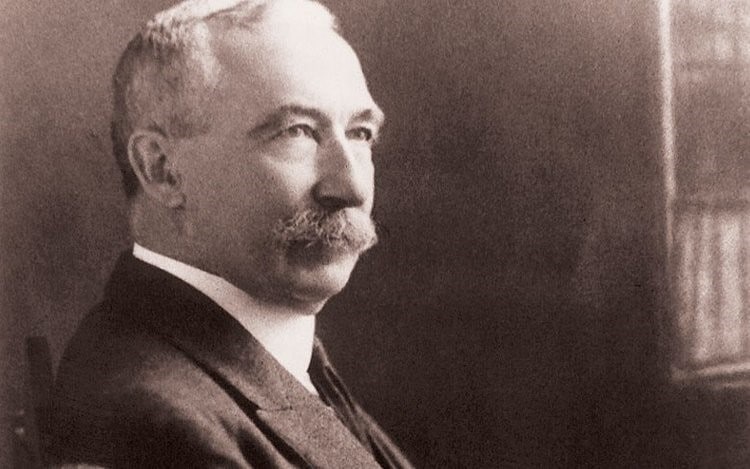

Sir Robert McCarrison (1878-1960) was a British physician who spent most of his career in India, studying a variety of medical problems. One of his earliest studies was on goiter, which he determined was caused by a combination of iodine deficiency and an infectious agent in the drinking water. He proved this by drinking water from the polluted spring and producing goiters in 10 out of 36 volunteers — including himself.

By 1914, the discovery of vitamins and their connection to deficiency diseases was one of the hottest topics in medical science, and McCarrison started doing his own experiments with pigeons, guinea pigs and monkeys. In one of his studies, he found that monkeys fed autoclaved rice and other foods died rapidly, while those fed a non-autoclaved diet of whole wheat bread, milk, groundnuts, onion, butter, and plantains remained healthy. While doing such research on monkeys would certainly be frowned upon today, it demonstrated that a diet of sterilized food could not sustain life.

McCarrison conducted similar experiments on vitamin B deficiency in pigeons and vitamin C deficiency in guinea pigs. He compiled the results from all these feeding studies in a 1921 book called Studies in Deficiency Disease. He felt that, while the diets he had fed his experimental animals were obviously extreme, milder forms of vitamin deficiency might be responsible for many common ailments plaguing the British population — problems like dysentery, dyspepsia, colitis, ulcers and possibly celiac disease.

In support of this theory, McCarrison cited several examples of how therapy with vitamin-containing “protective foods” seemed to cure baffling ailments in some of his patients. One man, whom McCarrison described as a “martyr to dyspepsia,” had been eating an over-cooked diet deficient in fruits and vegetables. McCarrison noticed that this diet was “very similar to that of my monkeys” and helped the man transition to eating milk, eggs, cheese, fish, fresh meat, fresh fruit, green vegetables, and whole wheat bread. Within two and a half months, the man’s health was greatly improved.

Another way that McCarrison used these experimental results to help people was in the prevention of beriberi in the Pagan Jail in Burma. The prisoners in this jail were eating a diet dangerously deficient in vitamin B (mostly white rice). McCarrison advised the jail to replace half of the rice with whole wheat flour and to add “an abundance of root and green leafy vegetables.” The change was dramatic: beriberi ceased to be a problem, even in the winter; the prisoners liked the new diet better; and their health greatly improved.

McCarrison’s most famous nutritional study of all was done at the Nutrition Research Laboratories that he established at Coonoor, a town in the beautiful Nilgris or Blue Mountains in southern India. Here he maintained a population of over a thousand lab rats, which he used for studies to determine the effects that different diets might have on health.

McCarrison fed rats seven different diets, corresponding to those eaten by seven people groups in India: the Sikhs, Pathans, Mahrattas, Goorkhas, Bengalis, Kanarese and Madrassi. He found marked differences in the health of rats fed these different diets, with those given the Sikh diet the healthiest and those on the Madrassi diet the sickest. This was consistent with the health of the people groups themselves, leading McCarrison to conclude that the real differences between their physical fitness and health were nutritional, not racial.

The healthiest rats were those eating the Sikh diet, which consisted of whole wheat chapattis (unleavened bread) with fresh butter, sprouted Bengel gram (a legume), raw vegetables, milk, and meat once a week. The sickest rats were fed the Madrassi diet, which McCarrison said in his 1961 book Nutrition and Health “was made up of washed polished rice, dhal (legume), fresh vegetables, condiments, vegetable oil, coffee with sugar and a little milk, a little buttermilk, ghee (sparingly), coconut, betel-nut and water.”

Perhaps more shocking and pertinent to McCarrison’s British and American readers was his finding that rats fed a diet “eaten by many Western people of the poorer classes” were in just as bad of shape as those on the Madrassi diet. This bad diet was comprised of white bread, vegetables cooked in water to which sodium bicarbonate had been added, margarine, canned meat, sweetened tea and water.

From these experiments, McCarrison felt like he had plenty of experimental evidence to recommend what was a good diet for humans, and the typical British or American diet was not it! “All things needful for adequate nourishment of the body and for physical efficiency are present in whole cereal grains, milk, milk products, legumes, root and leafy vegetables and fruits, with egg or meat occasionally,” he concluded. In addition to his rat studies, he cited the superb health of the Indian people groups who ate such diets.

Research on deficiency diseases continued after McCarrison retired from the Nutrition Research Laboratories in 1935. Subsequent researchers discovered that some of the worst malnutrition in India occurred in “children’s hostels and boarding schools,” which were “museums for the study of malnutrition and deficiency disease.” When the researchers gave the supervisors of these boarding schools nutritional advice, the health of the children dramatically improved.

McCarrison meets Howard

After McCarrison retired, he returned to England, where he soon became connected to a movement of physicians and nutritionists who were concerned about the general ill health of the British populace. Most nutritionists of the time agreed that a deficient, overly-processed diet caused many non-infectious diseases which could be prevented by eliminating white flour and sugar and increasing consumption of vitamin-rich “protective foods”: milk, green leafy and orange vegetables and fruits, whole grains, and organ meats (especially liver and cod liver oil).

In 1939, a group of 600 family physicians, farmers, clergy, and schoolteachers, mostly from Cheshire County, England, met together in the Crewe Theatre. This meeting, sponsored by the Cheshire Medical Committee, was convened for the specific purpose of addressing the impact that poor nutrition might be having on chronic ill health.

There were two keynote speakers at this meeting. The first was Sir Robert McCarrison, who spoke about his rat studies in India and the effect that diet had on health. Consistent with the work of other contemporary researchers like Weston Price, the Cheshire Medical Committee and McCarrison concluded that a wide range of diets were capable of sustaining good human health — provided “that the food is, for the most part, fresh from its source, little altered by preparation and complete.”

So far, this was in accord with the views of other nutritionists of the time. But the Cheshire Medical Committee decided to go one step further and point out that these native diets, in addition to being fresh and unprocessed, were all produced without the aid of chemical fertilizers. That was where the second keynote speaker came in. Another British scientist who had spent his career in India, Sir Albert Howard, spoke about how the composting method that he had developed at the Indore Research Station improved soil and plant health.

Howard was a dynamic speaker; the audience was “spellbound” as he described how he had developed his composting method. As Lionel Picton observed in his 1949 book Nutrition and the Soil: Thoughts on Feeding, “That night, in the minds of the audience, the images of chemical agriculture and pest control, to whose shrines three generations of farmers have been assiduously directed, lay shattered to fragments.”

It was not enough to eat a healthy diet; it must be grown on healthy soil; and chemical fertilizers could not maintain soil health and might actually be detrimental to it. At least, that was what the Cheshire Medical Committee concluded after hearing Howard’s passionate speech. They would still focus on improving people’s diets, but in order to really get rid of deficiency diseases, they also needed to transition British agriculture to organic methods. As Howard wrote in his 1940 book An Agricultural Testament, “If bad farming is a factor in the production of poor physique and health, we must set about improving our agriculture without delay.”

Weighing the Evidence

Not surprisingly, Howard’s contention that chemical fertilizers produced food that was somehow nutritionally deficient was very controversial, stimulating a huge amount of research. Scientists quickly discovered that organically grown produce did not have significantly higher levels of measurable nutrients, like vitamins or minerals. From a reductionist perspective, there really was no difference between organic and conventional produce — just like, in a laboratory analysis, there was no difference between mineral nutrients from organic or chemical fertilizers.

Howard himself admitted that there wasn’t much reductionist scientific evidence for his claim that food grown on healthy soils was healthier. Instead, he and other early organic leaders relied on case studies for evidence. One of the most frequently cited examples was the exceptionally good health of the Hunzas, a people group in northern India. The Hunzas ate a similar diet to the Sikhs in McCarrison’s experiments and were reputed to be exceptionally healthy, plagued by none of the degenerative diseases of modern civilization. To grow this nutritious diet, they composted organic wastes and irrigated their fields with mineral-rich water from melting glaciers.

The problem with this particular case study was that Sir Albert Howard had never personally visited the Hunzas. He got all his information about them from a book by G. T. Wrench called The Wheel of Health. But Wrench had never seen the Hunzas, either; in fact, none of the organic leaders who cited this particular case study had ever met a real live Hunza or visited their village to see these farming methods firsthand.

The Hunzas aside, Sir Albert Howard and the Cheshire Medical Committee had plenty of other case studies to support their theories. They gave many examples of boarding schools where the health of children dramatically improved when they started growing their own fresh vegetables using organic methods. The headmaster from St. Martin’s School in Sidmouth wrote to Howard that his boys ate an “abundance of fruit and vegetables” grown with manure and compost and were exceptionally healthy compared to boys at other schools.

Then there was the bacon factory in Cheshire, where the manager decided to transform “waste land” around the buildings “into a model vegetable garden by means of compost made partly from the wastes of the factory.” In the factory cafeteria, employees were served potatoes and other vegetables grown on this land, as well as being given only whole wheat bread. “Already the health, efficiency, and well-being of the labor force has markedly improved,” Howard wrote in his 1945 book Farming and Gardening for Health or Disease.

Every other example that Howard, Picton and others gave to prove the superiority of organic produce was on these same lines. A hospital, school, institution or individual suffered from chronic ill health. Usually they ate a typical diet of white bread, sugar, some meat, and little milk or vegetables. The change came when they began growing fresh, organic vegetables, which were undoubtedly of superior quality to the limited quantity of wilted produce previously obtained from the market. Concurrent with increased consumption of vegetables, the diet was usually altered to include 100 percent whole wheat bread and increased quantities of whole milk, often raw milk. Invariably, the health, alertness, and attentiveness of those eating the new diet improved.

There were enough of these case studies to seem to show that a diet rich in fresh vegetables, whole grains, and milk was healthy — exactly what nutritionists had been saying for 20 years. Intriguingly, modern studies on the connection between organic food consumption and human health show similar results—many people who consistently consume organic foods have a lower incidence of degenerative diseases, but these same people also eat an overall healthy diet with a lot of “protective foods.” Trying to separate the effects of organic food and a healthy, minimally processed diet is still difficult, if not impossible.

Maybe part of the difficulty in determining whether organic food is healthier is that many modern people have a different definition of “organic” than the Cheshire Medical Committee did. To many consumers today, the primary danger in conventional produce is pesticides; hence, they assume that organic food, which does have significantly lower pesticide residues than conventional food, is automatically healthy.

But the Cheshire Medical Committee was just as worried about what had been taken out of conventional processed foods as what chemicals might have been added to them. Sir Albert Howard would likely have been shocked to see modern stores selling certified organic white sugar, white flour, and processed foods made from those ingredients. White flour and sugar were the antithesis of the “fresh produce from fertile soil” that Howard promoted.

All of the early organic leaders emphasized that agricultural production practices were only the first step in a holistic system that connected consumers to the soil as directly as possible, bypassing the modern food processing system that had caused the health problems the Cheshire Medical Committee was trying to combat. And in every case study that seems to show that organic food is healthier, it has always been part of a balanced, minimally processed diet.

Anneliese Abbott is a graduate student in the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She holds a B.S. in plant and soil science from The Ohio State University and is the author of Malabar Farm: Louis Bromfield, Friends of the Land, and the Rise of Sustainable Agriculture. She can be contacted at amabbott@wisc.edu.”

About Eco Farming Daily

EcoFarmingDaily.com is the world’s most useful farming, ranching and growing website. Built and managed by the team at Acres U.S.A., the Voice of Eco-Agriculture, all our how-to information is written by research authors, livestock professionals and world-renowned growers. Join our community of thousands using this information to build their own profitable, ecological growing systems.